It does seem that parish ministry and itinerancy as models of Christianization are quite distinct from each other. The first emphasizes a ‘settled’ ministry with a pastor or pastors within a fixed geographic locale, drawing the unconverted within that charge to the sound of the Gospel call – and so into the regular worship services of the church – by a regular, habitual, and personal (often life-long) labor. Evangelization was by preaching, yes, but preaching that worked hand-in-hand with the methodical visitation of the unconverted in a defined territory, in coordination with other parochial ministers in their settled charges. This, as far as I understand it, was the norm in Reformation and Post-Reformation Scotland, for example. The second presumes an ‘unsettled’ ministry in a geographic area with a great spiritual need and sends men in circuits throughout that region to preach until such a time as regular, settled ministries can be established.

The two models have not always lived in peaceful coexistence. The First and Second Great Awakenings, as I’ve heard, introduced tensions on this subject. The itinerancy of great preachers such as Whitfield was warmly embraced by some, such as Jonathan Edwards, and even by many of the Scots Presbyterians (for a time). But there were many questions lingering as to whether the sensationalism of the comet-preachers with their big, spellbound crowds detracted from the value of the regular, settled ‘parish’ ministers. Did it all tend to remove the ancient boundary marks? Did it in any way contribute to a more market-oriented, consumerist Christianity, which figures such as Thomas Chalmers deplored? A brand of Christianity that focuses upon attracting those already religiously predisposed and fails to go after – habitually and methodically – the indifferent and careless? Perhaps.

But are parish ministry and itinerancy in and of themselves mutually exclusive models? Must we choose one over the other? Are Thomas Boston and Robert Murray M’Cheyne automatically good because they were arduous, settled parish ministers, given to systematic household visitation of all within their charge? Were Whitfield and the American frontier circuit riders automatically bad because they refused to settle down to the parson’s life? While I reject the idea that we should reimplement all the methods of the apostles in those formative days of the Gospel in the 1st century Mediterranean world, including ‘episcopal’ itinerancy and the deployment of apostolic deputies, yet isn’t there something to be said for the lawfulness of a kind of itinerancy during times of unusual need? When elders weren’t raised up in established congregations, Paul and his deputies visited – and appointed ‘settled’ elders. He left to Timothy a model for the continuation of the regular ministry, foreseeing a day when unsettled itinerants would no longer be necessary. Much like scaffolding to a finished building, the itinerant ministry was there for a time until the finished product could stand. Or, like parents to a child until he becomes mature enough to make it on his own.

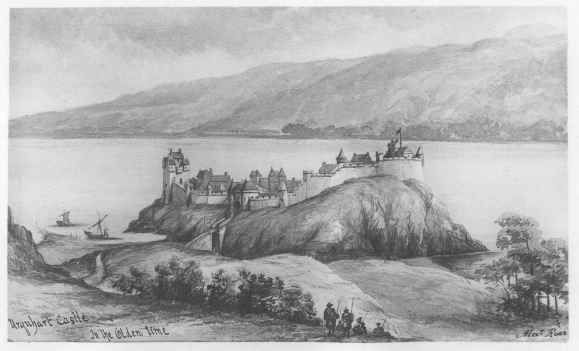

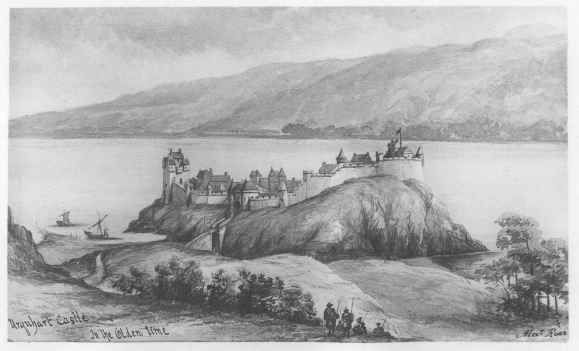

The 16th century Church of Scotland in the First Book of Discipline made use of ‘superintendants’ to preach, establish new congregations, and ordain ministers throughout large geographical areas, during an extraordinary time when there was a shortage of ministers and the work of evangelizing the nation was a pressing need. And while the Lowlands had been effectively Christianized by the 17th century, yet the Highlands were still under the sway of Rome. The settled parish system of the south could not be easily managed in the north, where the vast, mountainous ‘parishes’ of the Highlands were too difficult to reduce to the order of a settled charge. Consequently the Established Church utilized itinerant ‘catechists’ in the Highlands through agencies such as the Scottish Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge (SPCK – incidentally, which also helped fund David Brainerd’s efforts to the Delaware Indians of North America).

Perhaps we may view itinerancy and parish ministry as complementary strategies, given different stages of an offensive. The first is a strategy for quick, broad dissemination of the Gospel of the Kingdom. It is the ‘first strike’ against the Kingdom of Darkness. It establishes the beachhead. Outposts are established in enemy territory. Then the second strategy is phased in. Theses outposts serve as bases to advance the frontline in their respective zones, and all in cooperation with each other. They do not interfere in the zone of another outpost, but fully expect the other to take possession of theirs, as they themselves are busy doing the same from their position. After all, they are fighting a common enemy.

One might think that in itinerancy geography factors less prominently than in parochialism. Itinerancy does not methodically focus on fixed households in a given district; parochialism does. Itinerancy relies mostly upon indiscriminate preaching sporadically in an area, sowing seed broadly; parochialism does not, since it concentrates regularly in one particular area.

But it is not as though geography is less of a concern in itinerancy. The Apostle Paul was an itinerant, it is true. “From Jerusalem, and round about unto [kuklo mechri, lit., ‘in a circuit’] Illyricum, I have fully preached the gospel of Christ” (Rom. 15:19). But note his great concern with localities, areas, regions, and even political territories – nations, along his routes. “As the truth of Christ is in me, no man shall stop me of this boasting in the regions [en tois klimasin] of Achaia” (2 Cor. 11:10). He was claiming lands for the Redeemer, and even had his eyes set on the frontiers – Spain (Rom. 15:24). Territories were divided up, and Corinth belonged to Paul. “But we will not boast of things without our measure, but according to the measure of the rule [to metron tou kanonos – ‘the boundary lines?’] which God hath distributed [emerisen] to us, a measure to reach even unto you. . . having hope, when your faith is increased, that we shall be enlarged by you according to our rule [ta kanona hemon] abundantly, to preach the gospel in the regions beyond you [ta hyperekeina]” (2 Cor. 10:13-16). Corinth then, to use much later Presbyterian jargon, was ‘within his bounds.’ (I cannot help but envision Paul with his deputies poring over a map of the Mediterranean as a general would with his officers!) So it is clear that itinerancy is not necessarily un-geographic in orientation.

One might also conclude that preaching is given a greater place in itinerancy and less in parochialism. It is always through the foolishness of preaching that God saves, whether in more or less settled phases of the Kingdom of God in a certain territory. But even itinerant ministry is not just about getting on a soapbox and preaching to anyone and everyone who might walk by. It also involves interpersonal, private interaction. The Apostle Paul both “taught publicly” in his Gospel labors in Ephesus as well as “from house to house” (Acts 20:20). Paul dealt intimately with the Philippian jailor and his household (Acts 16:32). And our Lord Himself, though an itinerant preacher, dealt privately with Nicodemus (John 3:1-13) and the Samaritan woman (John 4:1-30). Nor is parochial ministry all private visitation. Paul, writing to his deputy Timothy, was to focus on regular public ministry in Ephesus. “Till I come, give attendance to reading, to exhortation, to doctrine” (1 Tim. 4:13). “Preach the word; be instant in season, out of season; reprove, rebuke, exhort with all longsuffering and doctrine” (2 Tim. 4:2). And in addition to preaching, he was to train men who could settle into Timothy’s place, continuing the same, regular, public ministry of the Word (2 Tim. 2:2). The main difference here between the two models, it would seem, lies in the fact that the itinerant ministry is not settled, dealing regularly with the same number of people in a locality for a long period of time whereas the other is. And I also suppose that there is a certain fluidity between the itinerant and settled parochial ministry, especially since Paul stayed ministering in Ephesus for two years (Acts 19:9) and while under house arrest in Rome used his rented house to preach regularly there (Acts 28:30, 31).

But while there are differences and distinctions to be made between the two models or strategies, in one thing they are identical. Both are evangelistically oriented. There is no retreat into the insulated comfort of the congregation of the faithful, but both manifest an impetus beyond.

Read Full Post »

Writing more than a century before the McDonaldization of the Church, Thomas Chalmers (1780-1847) exposed the fallacy of faith in structures for evangelization. It is a “Quixotic imagination, that on the strength of churches alone, viewed but in the light of material apparatus, we were to Christianize the population – expecting of these new erections, that, like so many fairy castles, they were, of themselves, to transform every domain in which they were placed into a moral fairyland” (Works 18:109). While perhaps most evangelicals would probably deny the bald proposition that the building can birth a believer, yet it is very easy subconsciously to think that outward can allure the natural man out of his state of spiritual rebellion. The fact is, if you build it, they just won’t come. It is fleshly to think otherwise, for the arm of the flesh – and the fleshly mind – are powerless.

Writing more than a century before the McDonaldization of the Church, Thomas Chalmers (1780-1847) exposed the fallacy of faith in structures for evangelization. It is a “Quixotic imagination, that on the strength of churches alone, viewed but in the light of material apparatus, we were to Christianize the population – expecting of these new erections, that, like so many fairy castles, they were, of themselves, to transform every domain in which they were placed into a moral fairyland” (Works 18:109). While perhaps most evangelicals would probably deny the bald proposition that the building can birth a believer, yet it is very easy subconsciously to think that outward can allure the natural man out of his state of spiritual rebellion. The fact is, if you build it, they just won’t come. It is fleshly to think otherwise, for the arm of the flesh – and the fleshly mind – are powerless.

Some time back I was listening to a prominent Reformed speaker. He contended that while our confessions and catechisms were right and useful, yet we tend to freeze-dry them and rigidly force them into cultural contexts where they are not always immediately relevant. He suggested that we need to be sensitive to the questions that the culture is asking in which we minister. Those questions may not be the same as those that have historically been asked.

Some time back I was listening to a prominent Reformed speaker. He contended that while our confessions and catechisms were right and useful, yet we tend to freeze-dry them and rigidly force them into cultural contexts where they are not always immediately relevant. He suggested that we need to be sensitive to the questions that the culture is asking in which we minister. Those questions may not be the same as those that have historically been asked.