“A Plea and Plan for a Coöperative Church Parish System in Cities,” by Walter Laidlaw

In this essay, published in the American Journal of Sociology (1898), Walter Laidlaw advocates among the Protestant church a voluntary ‘cooperative parish system’ in the large cities of the United States for the spiritual, moral, and socio-economic benefit of the people. His argument is threefold. First, it is the mandate of Christ to seek the entire well-being of men, both body as well as soul. Secondly, Laidlaw contends that the Church owes it to the taxpayers to seek the ‘moral uplift’ of the working classes. They ought not receive tax exemption for nothing in return. Quite an interesting take on the role of the Church in relation to a non-establishmentarian state! Last, the particular plan he advocates is the surest way to satisfy the mandates both of heaven and of earth.

Positively, I think the article reproduces both the zeal of Thomas Chalmers on the need of Church to evangelize (and that wholistically) the burgeoning modern cities and his level-headed practicality in how the work ought to be done. Energetic, cooperative territorialism is the answer. While Chalmers is not mentioned, his fingerprints are all over it.

Positively, I think the article reproduces both the zeal of Thomas Chalmers on the need of Church to evangelize (and that wholistically) the burgeoning modern cities and his level-headed practicality in how the work ought to be done. Energetic, cooperative territorialism is the answer. While Chalmers is not mentioned, his fingerprints are all over it.

Further, Laidlaw certainly continued this legacy by endorsing the elevated philanthrophy that gives intelligently.

My only qualm is the faint note of evangelicalism throughout. It is there, but it is too subdued for my comfort. Presently, I’ve not found out much about Laidlaw’s theology (if anyone can shed some light, I would welcome it). I’m not sure whether he was an advocate of the Social Gospel or whether he retained a distinctive evangelical stance. But the essay is almost altogether devoted to the cooperative parish plan for the relief of outward human misery. I would say ‘Amen and Amen’ to Laidlaw if he unequivocally made the efficient dissemination of the apostolic Gospel the ultimate justification of the system. But right now, I’m at just one ‘Amen.’

Below are some great quotes, with a few comments interspersed.

* * * * * * *

“Originated by the Holy One from one of the largest cities of Judah, commissioned in Palestine’s largest city, her literature christened with the names of the ancient world’s greatest cities and city, her social ideal a city let down from heaven, the church has the opportunity to take the primacy, beyond all question, in altruistic movements, by the institution of a coöperative parish system in cities” (796).

Lamenting over the relative failure of Protestant over Roman Catholic churches to retain their adherents in the large cities, Laidlaw writes,

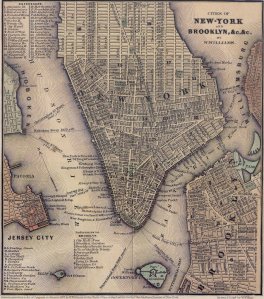

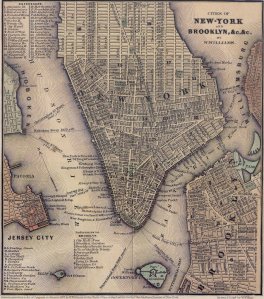

“Protestantism’s families are not in Protestantism’s church because Protestantism’s church representatives, attending to the people on their communion and pew rolls, scattered all over the 13,000 acres of Manhattan island, have not time or plan to discover and recover the families found on no communion or pew roll.

“It should be a humiliation to Protestantism in New York that three Roman Catholic churches get at more families in the district than do ninety-five Protestant churches, among which are three resident churches. It is idle to ascribe the difference of efficiency in the district to denominational tendency, or national characteristics. It is rather due to the difference between regimentation and somnambulism [sleepwalking]. “Except the Lord keep the city, the watchmen waketh but in vain,’ says Protestantism; and she does on underestimating human wide-awakeness and gumption through her admirable reverence for divine grace. She walketh in a dumb show of saving the city for herself or her Lord” (799-800).

Appreciating the work of the Evangelical Alliance (itself a brainchild of Chalmers) before him in seeking to bring the Gospel wholistically to the cities, Laidlaw critiques the over-idealism of a previous plan that had doomed it to failure. That plan failed in part precisely because of an overemphasis on cooperation:

“It is too ideal … in intermingling denominational visitors. The first step to be taken would [rather] seem to be to induce the churches to regard a geographical area as a special responsibility, and many a church would undertake this if, as a church, it were held responsible for the area, when it might not be willing to share the responsibility with workers from other churches. Spiritual life is systole and diastole indeed, both organization and individual discharging both organic functions at time, but if the church is a divine organization, we must concede her arterialism and assume that individuals are venous” (801).

“Christianity’s warm heart will say to her cool head, when she sees that her alms and uplift must be with both left hand and right hand: ‘Had, you must direct this business for me, or I shall fail in meeting this need. The Master himself did not feed the multitude by Galilee as a mob. He divided the five thousand into companies, and gave each of the twelve his sections to care for. And they did all eat and were filled, no one was overlooked. And they gathered up twelve baskets of fragments, a basket for each disciple, more food than they started with. Head, this need is so great that some hungry one is sure to be underfed, and some greedy one is sure to be overfed, unless there is method.’ And when Christianity talks in this strain, it will not indicate a cooling heart, but a glowing one, one that responds to the Redeemer’s desire, and ‘mind and soul, according well, / will make one music as before’” (803).

Last, Laidlaw gives a number of guidelines for such a cooperative parish system. Cooperation is more than inter-church – it also involves cooperation with civic officials for the ultimate blessing of the community. He gives one interesting instance of such cooperation in New York City during his time:

“For instance, the committee on parks recently circulated a petition, signed by everyone of the pastors in the area, asking the city authorities to locate a small park in the region. When the park is actually opened, it cannot but advertise throughout the whole neighborhood the fact that the church is interested in the people’s well-being” (806-7).

Read Full Post »

one reads these verses in their context, not only is attention called to place, but place is given special significance.

one reads these verses in their context, not only is attention called to place, but place is given special significance. Positively, I think the article reproduces both the zeal of Thomas Chalmers on the need of Church to evangelize (and that wholistically) the burgeoning modern cities and his level-headed practicality in how the work ought to be done. Energetic, cooperative territorialism is the answer. While Chalmers is not mentioned, his fingerprints are all over it.

Positively, I think the article reproduces both the zeal of Thomas Chalmers on the need of Church to evangelize (and that wholistically) the burgeoning modern cities and his level-headed practicality in how the work ought to be done. Energetic, cooperative territorialism is the answer. While Chalmers is not mentioned, his fingerprints are all over it. this to say of him, “Herbert speaks to God like one that really believeth a God, and whose business in the world is most with God. Heart-work and heaven-work make up his books.” High praise, coming from the ‘Reformed Pastor’ himself!

this to say of him, “Herbert speaks to God like one that really believeth a God, and whose business in the world is most with God. Heart-work and heaven-work make up his books.” High praise, coming from the ‘Reformed Pastor’ himself!