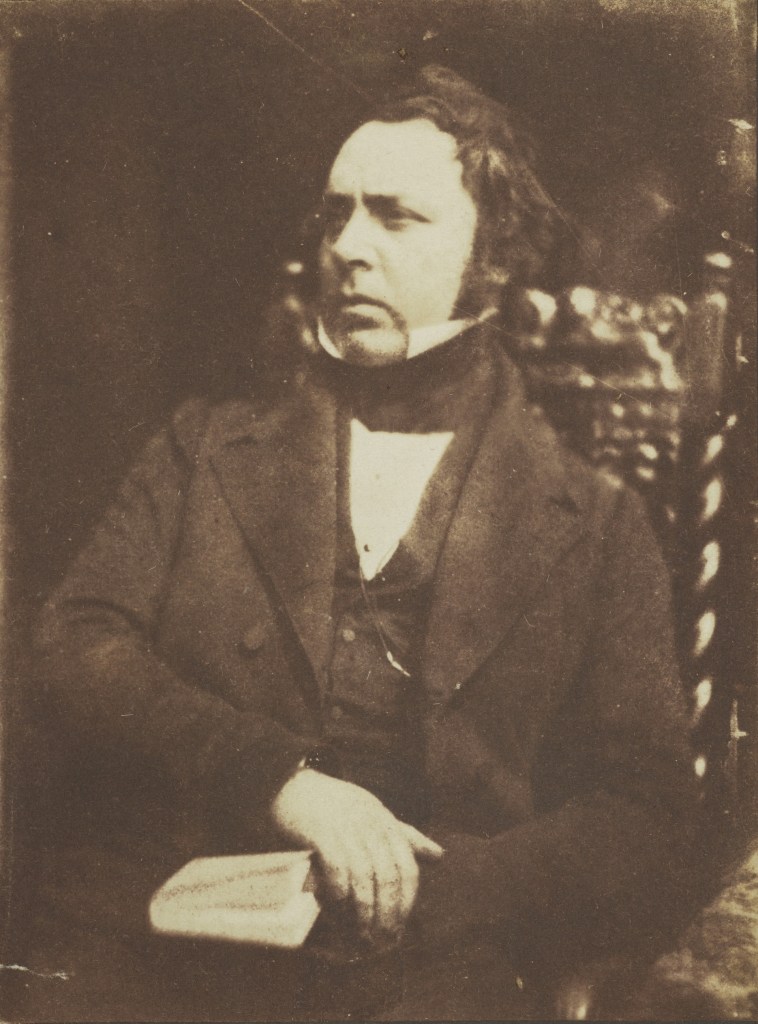

The following is an extract from Thomas Chalmers’ personal notes from house to house visitation in his first parish of Kilmany, with comment by William Hanna, editor of his Memoirs. It well illustrates the Scottish Reformed legacy of the spiritual care for all souls in a defined geographical area as well as the ancillary custom of pastoral journaling. Here are the records of a true, spiritual physician.

The following is an extract from Thomas Chalmers’ personal notes from house to house visitation in his first parish of Kilmany, with comment by William Hanna, editor of his Memoirs. It well illustrates the Scottish Reformed legacy of the spiritual care for all souls in a defined geographical area as well as the ancillary custom of pastoral journaling. Here are the records of a true, spiritual physician.

A few specifics are worthy of special observation. Note the frequent entreaties raised to the Lord, reminiscent of another memoir-writer, Nehemiah (Neh. 2:4, 5:19, 6:14, 13:14, 22, 29, 31). Here is one devoting himself to the ministry of the Word and prayer. We also should observe amid these ‘ejaculatory’ prayers an ongoing willingness to engage in self-criticism. May we too rest in the Lord for whom we labor, and not in our labors themselves. They are fraught with sin and imperfection – “but our sufficiency is of God” (2 Cor. 3:5).

Last, Hanna includes an overview of Chalmers’ practice of catechizing, in the well-worn path of the old Church of Scotland practice. His method was evidently very gracious and dialogical, yet it clearly honored the high authority vested in the Catechism’s biblical doctrines. Firmness in confession, pastoral finesse in method. A delicate balance indeed!

* * * *

“February 15th, 1813.—Visited Mrs. B., who is unwell, and prayed. Let me preach Christ in all simplicity, and let me have a peculiar eye on others. I spoke of looking unto Jesus, and deriving thence all our delight and confidence. O God, give me wisdom and truth in this household part of my duty.

“February 21st.— Visited at Dalyell Lodge. They are in great affliction for the death of a child. I prayed with them. O God, make me wise and faithful, and withal affectionate in my management of these cases. I fear that something of the sternness of systematic orthodoxy adheres to me. Let me give up all sternness; but let me never give up the only name by which men can be saved, or the necessity of forsaking all to follow Him, whether as a Saviour or a Prince.

“March 25th.— Visited a young man in consumption. The call not very pleasant; but this is of no consequence. O my God, direct me how to do him good.

“June 2d.— Mr. ——— sent for me in prospect of death; a man of profligate and profane habits, who resents my calling him an unworthy sinner, and who spoke in loud and confident strains of his faith in Christ, and that it would save him. O God, give me wisdom in these matters to declare the whole of thy counsel for the salvation of men. I represented to him the necessity of being born again, of being humbled under a sense of his sins, of repenting and turning from them. O may I turn it to my own case. If faith in Christ is so unsuitable from his mouth because he still loves sin, and is unhumbled because of it, should not the conviction be forced upon me that I labor myself under the same unsuitableness? O my God, give me a walk suitable to my profession, and may the power of Christ rest upon me.

“June 4th.— Visited Mr — again. Found him worse, but displeased at my method of administering to his spiritual wants. He said that it was most unfortunate that he had sent for me; talked of my having inspired him with gloomy images, but seemed quite determined to buoy himself up in Antinomian security. He did not ask me to pray. I said a little to him, and told him that I should be ready to attend him whenever he sent for me.

“August 9th.— Miss — under religious concern. O my God, send her help from Thy sanctuary. Give me wisdom for these cases. Let me not heal the wound slightly; and, oh, while I administer comfort in Christ, may it be a comfort according to godliness. She complains of the prevalence of sin. Let me not abate her sense of its sinful ness. Let me preach Christ in all his entireness, as one that came to atone for the guilt of sin, and to redeem from its power.

“March 15th, 1814.—Poor Mr. Bonthron, I think, is dying. I saw him and prayed, after a good deal of false delicacy. O my God, give me to be pure of his blood, and to bear with effect upon his conscience. Work faith in him with power. I have little to record in the way of encouragement. He does not seem alarmed himself about the state of his health, and, I fear, has not a sufficient alarm upon more serious grounds. It is a difficult and heavy task for me; and when I think of my having to give an account of the souls committed to me, well may I say, Who is sufficient for these things?

“March 23d.— Mr. Bonthron was able to be out, and drank tea with us. I broke the subject of eternity with him. He acquiesces; you carry his assent always along with you, but you feel as if you have no point of resistance, and are making no impression.

“March 26th and 27th.—Prayed each of these days with Mr. Bonthron. I did not feel that any thing like deep or saving impression was made. O Lord, enable me to be faithful!

“April 3d.—Visited John Bonthron.

“April 5th.—Prayed with more enlargement with John than usual. I see no agitations of remorse; but should this prevent me from preaching Christ in His freeness? The whole truth is the way to prevent abuses.

“April 6th and 8th Visited Mr. Bonthron.

“April 9th.—Read and commented on a passage of the Bible to John. This I find a very practicable, and I trust effectual way of bringing home the truth to him.”

The next day was the Sabbath, on the morning of which a message was brought to the manse that Mr. Bonthron was worse. While the people were assembling for worship, Mr. Chalmers went to see him once more, and, surrounded by as many as the room could admit, he prayed fervently at his bedside. No trace remains of another visit.

Prosecuting his earlier practice of visiting and examining in alternate years, he commenced a visitation of his parish in 1813, which, instead of being finished in a fortnight, was spread over the whole year. As many families as could conveniently be assembled in one apartment were in the first instance visited in their own dwellings, where, without any religious exercise, a free and cordial conversation, longer or shorter as the case required, informed him as to the condition of the different households. When they afterward met together, he read the Scriptures, prayed, and exhorted, making at times the most familiar remarks, using very simple yet memorable illustrations. “I have a very lively recollection,” says Mr. Robert Edie, “of the intense earnestness of his addresses on occasions of visitation in my father’s house, when he would unconsciously move forward on his chair to the very margin of it, in his anxiety to impart to the family and servants the impressions of eternal things that so filled his own soul.” “It would take a great book,” said he, beginning his address to one of these household congregations, “to contain the names of all the individuals that have ever lived, from the days of Adam down to the present hour; but there is one name that takes in the whole of them—that name is sinner: and here is a message from God to every one that bears that name, ‘ The blood of Jesus Christ, His Son, cleanseth us from all sin.'” Wishing to tell them what kind of faith God would have them to cherish, and what kind of fear, and how it was that, instead of hindering each other, the right fear and the right faith worked into each other’s hands, he said, “It is just as if you threw out a rope to a drowning man. Faith is the hold he takes of it. It is fear which makes him grasp it with all his might; and the greater his fear, the firmer his hold.” Again, to illustrate what the Spirit did with the Word: “This book, the Bible, is like a wide and beautiful landscape, seen afar off, dim and confused; but a good telescope will bring it near, and spread out all its rocks, and trees, and flowers, and verdant fields, and winding rivers at one’s very feet. That telescope is the Spirit’s teaching.”

His own records of one or two of these visitations are instructive:

“February 18th, 1813.—Visited at Bogtown, Hawkhill, and East Kinneir. No distinct observation of any of them being impressed with what I said. At East Kinneir I gave intimation that if any labored under difficulties, or were anxious for advice upon spiritual and divine subjects, I am at all times in readiness to help them. Neglected this intimation at Hawkhill, but let me observe this ever after.

” February 16th.— A diet of visitation at ——. Had intimate conversation only with M. W. I thought the —— a little impressed with my exhortation about family worship, and the care of watching over the souls of their children. I should like to understand if —— has family worship.

” March 9th.—Visited at ——. The children present. This I think highly proper, and let me study a suitable and impressive address to them in all time coming.

“May 19th.— Visited at ——. I am not sure if Icould perceive any thing like salutary impression among them; but I do not know, and perhaps I am too apt to be discouraged. C. S. and J. P. the most promising. O my God, give me to grow in the knowledge and observation of the fruits of the Spirit and of His work upon the hearts of sinners.

“August 9th—Visited at Hill Cairney. Resigned myself to the suggestions of the moment, at least did not adhere to the plan of discourse that I had hitherto adopted. I perceived an influence to go along with it. O my God, may this influence increase more and more. I commit the success to Thee.”

In examining his parish he divided it into districts, arranging it so that the inhabitants of each district could be accommodated in some neighboring barn or school-house. On the preceding Sabbath all were summoned to attend, when it was frequently announced that the lecture then delivered would form the subject of remark and catechizing. Generally, however, the Shorter Catechism was used as the basis of the examination. Old and young, male and female, were required to stand up in their turn, and not only to give the answer as it stood in the Catechism, but to show, by their replies to other questions, whether they fully understood that answer. What in many hands might have been a formidable operation, was made light by the manner of the examiner. When no reply was given, he hastened to take all the blame upon himself. “I am sure,” he would say, “I have been most unfortunate in putting the question in that particular way,” and then would change its form. He was never satisfied till an answer of some kind or other was obtained. The attendance on these examinations was universal, and the interest taken in them very great. They informed the minister of the amount of religious knowledge possessed by his people, and he could often use them as convenient opportunities of exposing any bad practice which had been introduced, or was prevailing in any particular part of his parish. Examining thus at a farm-house, one of the plowmen was called up. The question in order was, “Which is the eighth commandment?” ” But what is stealing?” “Taking what belongs to another, and using it as if it were your own.” “Would it be stealing, then, in you to take your master’s oats or hay, contrary to his orders, and give it to his horses?” This was one of the many ways in which he sought to instill into the minds of his people a high sense of justice and truth, even in the minutest transactions of life.

“November 30, 1813.—Examined at . J. W. and B. T. both in tears. The former came out to me agitated and under impression.

“January 20th, 1814.—Had a day of examination, and felt more of the presence and unction of the Spirit than usual.

“January 21st—Had a day of examination. Made a simple commitment of myself to God in Christ before entering into the house.

“February 8th—Examined, and have to bless God for force and freeness. D. absenting himself from all ordinances. Let me be fearless at least in my general address, and give me prudence and resolution, O Lord, in the business of particularly addressing individuals. I pray that God may send home the message with power to the people’s hearts.

“February 23d.—Examined ——. A very general seriousness and attention. B. and his wife still, I fear, very much behind.

“April 5th.—Examined at P. I can see something like a general seriousness, but no decided marks in any individual.

“March 8th.— Examined at S. The man P. B. deficient in knowledge, and even incapable of reading; the father of a family too. I receive a good account of ——. Oh! that they may be added to the number of such as shall be saved.

“July 2d.—Examined with more enlargement and seriousness. I feel as if there was an intelligence and good spirit among the people. O God, satisfy me with success; but I commit all to Thee.

“July 27th—Examined at ——. The family afraid of examination, I think, and they sent me into a room by myself among the servants. This I liked not; but, O God, keep me from all personal feeling on the occasion. I brought it on myself by my own accommodating speeches. I have too much of the fear of man about me. Never felt more dull and barren. I feel my dependence on God. I pray for a more earnest desire after the Christianity of my parish, and, oh may that desire be accomplished. O God, fit a poor, dark, ignorant, and wandering creature for being a minister of Thy word! Uphold me by Thy free Spirit, and then will I teach transgressors Thy ways.”

The family here referred to was that of a farmer recently settled in the parish, and who, unfamiliar with the practice of examination, felt at the first a not unnatural reluctance to be subjected to it. On his return to the manse, Mr. Chalmers jotted down the preceding impressive notice of his reception and its result. In the afternoon of the same day he went back to the family; told them that, as they had not come to him in the morning, he had just come to them in the evening to go over the exercise with themselves. The frank and open kindness of the act won their instant compliance, and brought its own reward.

Read Full Post »

I recently gave a lecture (sermon?) on the fascinating and inspiring story of Thomas Chalmers’ West Port Experiment in the slums of Industrial Edinburgh, from 1844-1847. You can listen to it

I recently gave a lecture (sermon?) on the fascinating and inspiring story of Thomas Chalmers’ West Port Experiment in the slums of Industrial Edinburgh, from 1844-1847. You can listen to it