I just read a great piece by Carl Trueman on the virtue of self-restraint when engaging in theological controversy. He essentially argues that we ought to be much more modest about our usefulness beyond the sphere God has placed us. Most of us ought simply to retire our capes, roll up our sleeves, and channel our energies our own small, local plot. While Trueman’s piece is by no means a formal endorsement of parochialism, my parochial mind can’t help thinking about Chalmers’ celebration of the “power of littles” and his famous dictum, “Locality, in truth, is the secret principle wherein our great strength lieth.” Chalmers also repeatedly burst the bubbles of the pretentious who thought they could and should assume larger fields of work. They ought rather be “sober minded” about their gifts and celebrate the giftings of others. And work. Locally.

I just read a great piece by Carl Trueman on the virtue of self-restraint when engaging in theological controversy. He essentially argues that we ought to be much more modest about our usefulness beyond the sphere God has placed us. Most of us ought simply to retire our capes, roll up our sleeves, and channel our energies our own small, local plot. While Trueman’s piece is by no means a formal endorsement of parochialism, my parochial mind can’t help thinking about Chalmers’ celebration of the “power of littles” and his famous dictum, “Locality, in truth, is the secret principle wherein our great strength lieth.” Chalmers also repeatedly burst the bubbles of the pretentious who thought they could and should assume larger fields of work. They ought rather be “sober minded” about their gifts and celebrate the giftings of others. And work. Locally.

Archive for the ‘Articles’ Category

Locality & knowing our limitations

Posted in Articles, Locality & the Law of Residence, Parish Theory & Practice, Parochial Strategy, Theology of Place, Thomas Chalmers on June 18, 2011| Leave a Comment »

The hidden beauty of family worship

Posted in Articles, Care for the Youth, Catechesis, Family Religion, Transgenerational Faith, WPE Editor on June 3, 2011| 5 Comments »

Let’s face it. Those of us who practice family worship frequently don’t feel like it, often fall into formalism, and end off hopping down way too many bunny trails. How many times, too, is the whole business interrupted because the little one has a runny nose (or worse, smelly drawers)? The boy isn’t sitting up? Or older sis is annoying the younger for the umpteenth time? And after a long day of homeschooling, errands, cleaning, and damage controlling, mom is frazzled – and dad is just plain socked. At its best, family worship is usually nondescript; at its worst, it approaches something like a three-ring circus.

Let’s face it. Those of us who practice family worship frequently don’t feel like it, often fall into formalism, and end off hopping down way too many bunny trails. How many times, too, is the whole business interrupted because the little one has a runny nose (or worse, smelly drawers)? The boy isn’t sitting up? Or older sis is annoying the younger for the umpteenth time? And after a long day of homeschooling, errands, cleaning, and damage controlling, mom is frazzled – and dad is just plain socked. At its best, family worship is usually nondescript; at its worst, it approaches something like a three-ring circus.

And yet, when we look back on it more impartially, we find that there has been glory there all along. After the drill is done – and done with some habit – we see in faith that the very rhythm itself has been wonderful. All the children know their places. The catechumens say their lines. The old songs of Zion are taken up and singing fills the room; and those who can’t read croon right along. The humble family Bible is taken out, and father reads a portion. And then the approach to the throne of grace.

Yes, it’s flawed. Messy even. And we must confess that it is fraught with sin. But it is covered in the blood and accepted by the Father. Let’s open our eyes – there is glory here. Things into which the very angels desire to look.

Small groups and Reformed ecclesiology

Posted in Articles, Church Order & Discipline, Ordinary Means Ministry on December 17, 2010| 11 Comments »

Small groups are immensely popular in evangelical circles these days, and increasingly commonplace in Reformed communions. I’m not sure how much of this is due to the influence of New Calvinism or whether it’s due to old-guard Reformed folk warming up to broader evangelicalism. Maybe both. Regardless of the source, it’s definitely a popular construct. Some would even argue that it’s a staple for ordinary church life.

I’ve been back and forth on small groups for some time. In my more skeptical moments, the following concerns have come to mind.

First, in classic Reformed ecclesiology – which in my judgment is radically biblical – where do small groups fit? They are not the public assembly, where the believers of a local communion “come together” to observe the corporate worship of God (Acts 14:27, 1 Cor. 11:17, 18, 20, 33, 34; 14:23, 26). And you can’t assign them to the private (Mat. 6:6, 14:23) or family devotion categories (Gen. 18:19, Deut. 6:4-9), since you can’t have a small group with one person or just one family. So if they are not in the three, traditional categories of worship/means of grace ministry (WCF 21.6), what place should they have?

I suppose an argument could be made that we can get them in the door by the body life argument. Small groups could be seen as a manifestation of koinonia, our sharing in the common life of the Spirit. Isn’t that Reformed? “Saints by profession are bound to maintain an holy fellowship and communion in the worship of God, and in performing such other spiritual services as tend to their mutual edification” (WCF 26.2). Well, I admit coming together for the Lord’s day services is not all there is to church fellowship. There is much to be done on a smaller scale and with more intimacy. Fine and good. “They that feared the Lord spoke often one with another, and a book of remembrance was written before him for them that feared the LORD, and that thought upon his name” (Mal. 3:16). But when informal, spiritual conversations transition into small groups, something changes. It is formalized, it requires organization, structure, and facilitation if not leadership. In short, it becomes programmatic. So if it is programmatic, where does it fit in the apostolic program? Is it a component of the ‘ordinary means?’

Second, there is the collective wisdom of our Reformed forbears. While I’m no expert in 16th and 17th century church history, it does appear that the Westminster Divines discouraged small groups from having a normative place in the life of God’s people. In fact, they appear to have been suspicious of them. “Whatsoever have been the effects and fruits of meetings of persons of divers families in the times of corruption or trouble, (in which cases many things are commendable, which otherwise are not tolerable,) yet, when God hath blessed us with peace and purity of the gospel, such meetings of persons of divers families (except in cases mentioned in these Directions) are to be disapproved, as tending to the hinderance of the religious exercise of each family by itself, to the prejudice of the publick ministry, to the rending of the families of particular congregations, and (in progress of time) of the whole kirk. Besides many offences which may come thereby, to the hardening of the hearts of carnal men, and grief of the godly” (Directory for Family Worship, Section 7).

Third, there is the obvious susceptibility of small groups to the influence of egalitarianism, feminism, and a host of other -isms. Clearly they are more vulnerable; and what is more, I have to wonder whether they are not in some ways the product of these extra-biblical spirits of the age.

So I ask the question – or to be more frank, I raise the doubt. For now, at least.

See also “More on My Allergy to Small Groups“

Real realpolitik

Posted in Articles, Church of Scotland, John Knox, Ministerial Fidelity on December 11, 2010| Leave a Comment »

John Knox, the great Scottish Reformer, was definitely no adept in worldly-wisdom. His positions were always unbending and uncompromising. He despised subtlety, and spoke always with the greatest of candor. He obviously had little interested in making friends and influencing people; that is, unless by influence one means shameless, hard-hitting argument!

John Knox, the great Scottish Reformer, was definitely no adept in worldly-wisdom. His positions were always unbending and uncompromising. He despised subtlety, and spoke always with the greatest of candor. He obviously had little interested in making friends and influencing people; that is, unless by influence one means shameless, hard-hitting argument!

When Queen Mary came to Scotland in 1561 to take the throne, she was of a mind to assert her royal prerogatives in everything – religion included. An ardent Romanist from her youth, she decided to make a clear, bold statement at the outset. She would have a mass celebrated in the chapel of the Holyrood house, something forbidden by the Protestant magistracy at the time.

Not surprisingly, Knox was outspoken against the celebration. There could be no accommodation, no middle ground. “One mass,” proclaimed Knox, “was more fearful unto him than if ten thousand armed enemies were landed in any part of the realm, of purpose to suppress the whole religion.”

One mass, Master Knox? One private mass, as a concession to the rightful heir of the throne? And that one mass should be of more dire consequence than a foreign invasion? Not only is this intolerant, but it’s unreasonable! Don’t you realize that to get what you want, you’ve got to give?

Knox responds to the naysayers. The mass issue is a non-negotiable, for “in our God there is strength to resist and confound multitudes, if we unfeignedly depend upon Him, of which we have had experience; but when we join hands with idolatry, it is no doubt but both God’s presence and defence will leave us; and what shall then become of us?”

What the calculators of this world can’t grasp is that he was more practical than them all! His explanation here reveals the deepest sagacic insight. Why? Because, thought Knox, you must factor God into every equation. Giving in to Queen Mary on one little point may have been expedient on the earthly plane in the short-run, but by doing so it would alienate the One whose favor is absolutely indispensable. You don’t want to mess with the ‘wrong man’ (or woman, in Mary’s case), but it’s far worse to mess with the ‘wrong God!’

Knox had learned his other-worldly wisdom at the feet of Wisdom incarnate. He, the Logos, the Light that lightens every man entering the world had said, “Whosoever shall seek to save his life shall lose it; and whosoever shall lose his life shall preserve it” (Lu. 17:33). To make it in this world and in the next, you must think counter-culturally, counter-intuitively. But be assured, this is the best way!

In deference to the One who “knows all things,” Knox shunned statescraft. But in doing so, he became the true patron and friend of the nation. If only we had eyes to see what Master Knox saw! If we would close our eyes and heed true Wisdom, we would walk the safest and most expedient course. And we would assign much less weight to earthly factors, which to the eye of the flesh loom so large.

The right questions: culture & catechism

Posted in Articles, Catechesis, WPE Editor on October 23, 2009| Leave a Comment »

Some time back I was listening to a prominent Reformed speaker. He contended that while our confessions and catechisms were right and useful, yet we tend to freeze-dry them and rigidly force them into cultural contexts where they are not always immediately relevant. He suggested that we need to be sensitive to the questions that the culture is asking in which we minister. Those questions may not be the same as those that have historically been asked.

Some time back I was listening to a prominent Reformed speaker. He contended that while our confessions and catechisms were right and useful, yet we tend to freeze-dry them and rigidly force them into cultural contexts where they are not always immediately relevant. He suggested that we need to be sensitive to the questions that the culture is asking in which we minister. Those questions may not be the same as those that have historically been asked.

Now, I don’t deny for a moment that each culture will come with its own set of questions, some of which we might consider ‘honest’ (cf. Acts 17:32). As stewards of the mysteries of God, we should wisely parcel out God’s truth to them, given their own particular histories, needs, and temptations. Further, the Reformed confessions and catechisms were certainly birthed in a context distinct in many ways from our own. Particular issues of the day pressed on our forebearers, conditioning their confessions and catechisms accordingly. Like the men of Isachaar, they “understood the times” (1 Chron. 12:32) and spoke winsomely to their generation.

The Settled Ministry & Itinerancy

Posted in Articles, Parish Theory & Practice, WPE Editor on June 4, 2008| Leave a Comment »

It does seem that parish ministry and itinerancy as models of Christianization are quite distinct from each other. The first emphasizes a ‘settled’ ministry with a pastor or pastors within a fixed geographic locale, drawing the unconverted within that charge to the sound of the Gospel call – and so into the regular worship services of the church – by a regular, habitual, and personal (often life-long) labor. Evangelization was by preaching, yes, but preaching that worked hand-in-hand with the methodical visitation of the unconverted in a defined territory, in coordination with other parochial ministers in their settled charges. This, as far as I understand it, was the norm in Reformation and Post-Reformation Scotland, for example. The second presumes an ‘unsettled’ ministry in a geographic area with a great spiritual need and sends men in circuits throughout that region to preach until such a time as regular, settled ministries can be established.

The two models have not always lived in peaceful coexistence. The First and Second Great Awakenings, as I’ve heard, introduced tensions on this subject. The itinerancy of great preachers such as Whitfield was warmly embraced by some, such as Jonathan Edwards, and even by many of the Scots Presbyterians (for a time). But there were many questions lingering as to whether the sensationalism of the comet-preachers with their big, spellbound crowds detracted from the value of the regular, settled ‘parish’ ministers. Did it all tend to remove the ancient boundary marks? Did it in any way contribute to a more market-oriented, consumerist Christianity, which figures such as Thomas Chalmers deplored? A brand of Christianity that focuses upon attracting those already religiously predisposed and fails to go after – habitually and methodically – the indifferent and careless? Perhaps.

But are parish ministry and itinerancy in and of themselves mutually exclusive models? Must we choose one over the other? Are Thomas Boston and Robert Murray M’Cheyne automatically good because they were arduous, settled parish ministers, given to systematic household visitation of all within their charge? Were Whitfield and the American frontier circuit riders automatically bad because they refused to settle down to the parson’s life? While I reject the idea that we should reimplement all the methods of the apostles in those formative days of the Gospel in the 1st century Mediterranean world, including ‘episcopal’ itinerancy and the deployment of apostolic deputies, yet isn’t there something to be said for the lawfulness of a kind of itinerancy during times of unusual need? When elders weren’t raised up in established congregations, Paul and his deputies visited – and appointed ‘settled’ elders. He left to Timothy a model for the continuation of the regular ministry, foreseeing a day when unsettled itinerants would no longer be necessary. Much like scaffolding to a finished building, the itinerant ministry was there for a time until the finished product could stand. Or, like parents to a child until he becomes mature enough to make it on his own.

The 16th century Church of Scotland in the First Book of Discipline made use of ‘superintendants’ to preach, establish new congregations, and ordain ministers throughout large geographical areas, during an extraordinary time when there was a shortage of ministers and the work of evangelizing the nation was a pressing need. And while the Lowlands had been effectively Christianized by the 17th century, yet the Highlands were still under the sway of Rome. The settled parish system of the south could not be easily managed in the north, where the vast, mountainous ‘parishes’ of the Highlands were too difficult to reduce to the order of a settled charge. Consequently the Established Church utilized itinerant ‘catechists’ in the Highlands through agencies such as the Scottish Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge (SPCK – incidentally, which also helped fund David Brainerd’s efforts to the Delaware Indians of North America).

Perhaps we may view itinerancy and parish ministry as complementary strategies, given different stages of an offensive. The first is a strategy for quick, broad dissemination of the Gospel of the Kingdom. It is the ‘first strike’ against the Kingdom of Darkness. It establishes the beachhead. Outposts are established in enemy territory. Then the second strategy is phased in. Theses outposts serve as bases to advance the frontline in their respective zones, and all in cooperation with each other. They do not interfere in the zone of another outpost, but fully expect the other to take possession of theirs, as they themselves are busy doing the same from their position. After all, they are fighting a common enemy.

One might think that in itinerancy geography factors less prominently than in parochialism. Itinerancy does not methodically focus on fixed households in a given district; parochialism does. Itinerancy relies mostly upon indiscriminate preaching sporadically in an area, sowing seed broadly; parochialism does not, since it concentrates regularly in one particular area.

But it is not as though geography is less of a concern in itinerancy. The Apostle Paul was an itinerant, it is true. “From Jerusalem, and round about unto [kuklo mechri, lit., ‘in a circuit’] Illyricum, I have fully preached the gospel of Christ” (Rom. 15:19). But note his great concern with localities, areas, regions, and even political territories – nations, along his routes. “As the truth of Christ is in me, no man shall stop me of this boasting in the regions [en tois klimasin] of Achaia” (2 Cor. 11:10). He was claiming lands for the Redeemer, and even had his eyes set on the frontiers – Spain (Rom. 15:24). Territories were divided up, and Corinth belonged to Paul. “But we will not boast of things without our measure, but according to the measure of the rule [to metron tou kanonos – ‘the boundary lines?’] which God hath distributed [emerisen] to us, a measure to reach even unto you. . . having hope, when your faith is increased, that we shall be enlarged by you according to our rule [ta kanona hemon] abundantly, to preach the gospel in the regions beyond you [ta hyperekeina]” (2 Cor. 10:13-16). Corinth then, to use much later Presbyterian jargon, was ‘within his bounds.’ (I cannot help but envision Paul with his deputies poring over a map of the Mediterranean as a general would with his officers!) So it is clear that itinerancy is not necessarily un-geographic in orientation.

One might also conclude that preaching is given a greater place in itinerancy and less in parochialism. It is always through the foolishness of preaching that God saves, whether in more or less settled phases of the Kingdom of God in a certain territory. But even itinerant ministry is not just about getting on a soapbox and preaching to anyone and everyone who might walk by. It also involves interpersonal, private interaction. The Apostle Paul both “taught publicly” in his Gospel labors in Ephesus as well as “from house to house” (Acts 20:20). Paul dealt intimately with the Philippian jailor and his household (Acts 16:32). And our Lord Himself, though an itinerant preacher, dealt privately with Nicodemus (John 3:1-13) and the Samaritan woman (John 4:1-30). Nor is parochial ministry all private visitation. Paul, writing to his deputy Timothy, was to focus on regular public ministry in Ephesus. “Till I come, give attendance to reading, to exhortation, to doctrine” (1 Tim. 4:13). “Preach the word; be instant in season, out of season; reprove, rebuke, exhort with all longsuffering and doctrine” (2 Tim. 4:2). And in addition to preaching, he was to train men who could settle into Timothy’s place, continuing the same, regular, public ministry of the Word (2 Tim. 2:2). The main difference here between the two models, it would seem, lies in the fact that the itinerant ministry is not settled, dealing regularly with the same number of people in a locality for a long period of time whereas the other is. And I also suppose that there is a certain fluidity between the itinerant and settled parochial ministry, especially since Paul stayed ministering in Ephesus for two years (Acts 19:9) and while under house arrest in Rome used his rented house to preach regularly there (Acts 28:30, 31).

But while there are differences and distinctions to be made between the two models or strategies, in one thing they are identical. Both are evangelistically oriented. There is no retreat into the insulated comfort of the congregation of the faithful, but both manifest an impetus beyond.

Baxter’s Bucerian Parish Reform

Posted in Articles, Experimental Religion & the Cure of Souls, Parish Theory & Practice, Richard Baxter on May 16, 2008| 1 Comment »

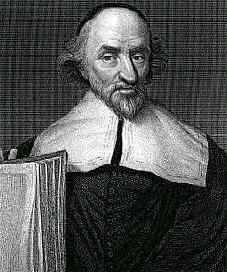

Portrait of Richard Baxter. King’s College London,

Foyle Special Collections Library

J. William Black, “From Martin Bucer to Richard Baxter: ‘Discipline’ and Reformation in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth Century England”

Anyone with a basic familiarity of the history of Protestantism will no doubt be acquainted with its leading personalities. Each of them had particular gifts, standing head and shoulders as Saul of Kish above their peers. And each contributed uniquely to the Church of their own as well as of the present day. Richard Baxter was certainly one of those figures, in whose shadow pastors of the present day still stand.

In this essay, Black renders a helpful service to us in the Reformation stream of pastoral theology. He traces the historical background for, the development, and the impact of Richard Baxter’s parish-based discipline, calculated to achieve the two-fold goal of the reformation of discipline in the Church of England and, simultaneously, the propagation of the gospel in the land. The program of Baxter’s involved, to put it concisely, “pastor-led and parish based … system of church discipline that would preserve the integrity of the sacraments and thus rob separatists of one of their primary excuses for abandoning the parochial system” (644).

According to Black, this was not a new paradigm, but one inherited from Martin Bucer, who in the 16th century sought to help the young Church of England establish a program that would reform the Church and Christianize the land. By refining discipline on the local level, the Church would be purified of its parish dross; by maintaining the parochial system of territorially defined ‘evangelistic’ (to use an anachronism) responsibility, the unconverted lump of the nation could effectively be leavened with the gospel. In this model, there are two concentric circles – the smaller, the Church, within the larger, the nation. By keeping these quite distinct and unblurred, the Church retains her spiritual integrity. By keeping the smaller self-consciously within and in reference to the larger, she retains her missiological purpose and vision. She must push the circumference of her circle increasingly towards the limits of the other in faithful obedience to the mandate of Christ.

Baxter simply borrowed this program and diligently implemented it. On the one hand, he set right to work removing the blur between congregation and parish by a faithful imposition of pastoral discipline. On the other hand, he did not cherry-pick ‘the best sort’ out of parish churches to form ‘gathered churches’ as the separatists did, leaving the parish spiritually to fend for itself. This would be to feed the sheep in the fold, yet leave Christ’s sheep as yet outside the fold without regular pastoral (evangelistic) concern. The Baxterian – or the Bucerian paradigm – retained both emphases without sacrificing one for the sake of the other. So Baxter was a nonconformist, one might say, in terms of church discipline and an establishment churchman in terms of national evangelistic responsibility and zeal.

The course by which Baxter achieved these ideals simultaneously was one that in the first place simply fell back to defining publicly the proper procedure for full adult communicant membership and publicly enforcing it. Black summarizes this policy, by which

the rights of adult church membership were made contingent upon a credible profession of faith and of consent to submit to pastoral oversight and discipline. Those who found themselves unfit for such a step could undergo a period of preparation to acquaint themselves with the fundamentals of Christian faith without calling their baptismal rights into question. The pastor could apply himself directly to helping them come to Christian faith and profession. Discipline would be exercised only on those who had willingly consented to place themselves under it. Thus the Lord’s Supper would be reserved for those in the parish who understood and professed the faith and who had willingly agreed to place themselves under the pastor’s oversight. The ignorant or otherwise ungodly members of the parish were excluded from the Lord’s Supper, but given a clear procedure by which they might become full adult members (664-65).

In the second place, for those not members yet in the parish the minister was obliged to solicit their spiritual change by an aggressive parochial visitation ministry.

Key also to Baxter’s program was cooperation or associationalism. This, we might say, would be a precondition for the twin ideals of local church discipline and parish evangelistic initiative. The existence of spheres of responsibility presumes a self-conscious understanding of distinct boundaries separating the them and us in the broader Church. What ethnically defined spheres of service were to Paul and Peter (Gal. 2:7-9), geographically defined ones were to English clergymen. And yet fences were not so much to divide as to unite. For by the division of labor geographically, the Church of England ministers would combine the aggregate of their mutual efforts to bear on the unsaved population. Let each have a portion dedicated to himself (Neh. 3), and the wall will be raised; let each build on his own foundation (Rom. 15:20-21), and the City of God shall stand. It was this conviction that led Baxter to found the Worcestershire Association and write extensively on church unity.

But cooperation was not only a precondition, but also a result of the church discipline/parish reclamation plan. By working in a non-competitive and cooperative way with other churchmen for the purging and the furtherance of the Church through the parish system, the case of Kidderminster was viewed as a replicable model for further similar ventures across the land. Kidderminster was a successful experiment of sorts, and Baxter was all too happy to see it inspiring others to work cooperatively for the greater good. He rejoiced to see that the Congregationalists and Baptists who

… had before conceited that Parish Churches were the great Obstruction of all true Church Order and Discipline … did quite change their Minds when they saw what was done at Kidderminster, and begin to think now, that it was much through the faultiness of the Parish Ministers, that Parishes are not in a better Case; and hat it is a better Work thus to reform the Parishes, than gather Churches out of them (670; quoted from Reliquiae Baxterianae 1:§136, 85-86).

Having recently studied Thomas Chalmers’ theory and practice of church extension, I can’t help but observe many lines of connection between these two great promoters of the parish ideal. Both were ardently concerned for ecclesiastical unity and cooperation, extensively collaborating with others beyond the bounds of their own denominational context. Both were staunch establishmentarians, eager to retain the preexisting parish system and to Christianize not only their parishes, but, by furnishing encouraging models for others to replicate, the entire nation and beyond (Black does not mention Baxter’s keen interest in overseas missions, such as that of John Eliot to the American Indians; but it is another striking parallel). Both were theorists as well as practitioners, arguing with the pen as much as with the hands and feet – Baxter gave us Kidderminster and Chalmers’ St. John’s and West Port. And both have left a lasting impact on modern day pastors and churches keen to see the reign of Christ manifested in individual souls, families, and their aggregates – societies, economies, and nations.

The paper does stimulate many further questions in my mind, but I will confine myself only to one, the problem of separation. This was a significant problem for Baxter (as well as Chalmers in the 19th century). Baxter sympathized with separatists because he saw first hand how corrupt many parish churches in the Church of England had become. The attraction of gathered churches was certainly strong among the truly godly. And yet Baxter excoriated them on the other hand for their detrimental policies. Black quotes Baxter:

Do not do as the lazy separatists, that gather a few of the best together, and take then [sic] only for their charge, leaving the rest to sink or swim. . . If any walk scandalously, and disorderly, deal with them for their recovery. . . . If they prove obstinate after all, then avoid them and cast them off; But do not so cruelly as to unchurch them by hundreds & by thousands, and separate from them as so many Pagans, and that before any such means hath been used for their recovery (The Saints Everlasting Rest, 509, emphasis mine).

So obviously Baxter was interested in a pure church: but not so pure that it cut off the world and buried its head ostrich-like in the sand before evangelistic duty.

But when does separation become necessary for Baxter? I have not studied him in great depth as of yet. But if I am correct, though a nonconformist liturgically, he was spared many of the hardships that others experienced who had sought first to reform the Church of England from within. And if the spirits of the godly in the Church of England were grieved at the profanation of the Lord’s Supper by the ungodly, did they have no other option than to move to Kidderminster or a similar parish? Is there not a point when, to use my earlier illustration, the integrity of the smaller circle is sacrificed for the well being of the larger? Black in this connection observes that, “While concerned to cope with the notoriously ungodly in their parishes, the more accommodating puritans were still hopeful that the existing parish system itself could be reformed. But even amongst these more patient puritans, there grew an increasing frustration with a structure and a hierarchy that seemed to fear more the implications of nonconformity and separatism than blatant hypocrisy and scandal at Communion” (652).

I speculate that perhaps Baxter was grieved more at the rush to separation without having first attempted the measures he successfully employed in his own context. Perhaps Baxter sniffed retreatism beneath surface claims of purism. And I also wonder whether the separatists would have satisfied him more (like Chalmers later) if they had after their break retained an ecclesiastically cooperative and territorially evangelistic approach. Whether they did or did not retain these ideals, or to what degree they did or did not, I cannot determine with my present knowledge. I would welcome any light on the matter.