“Yet I must say I liked the Irish part of my parishioners. They received me always with the utmost cordiality, and very often attended my household ministrations, although Catholics” (Works 16:243).

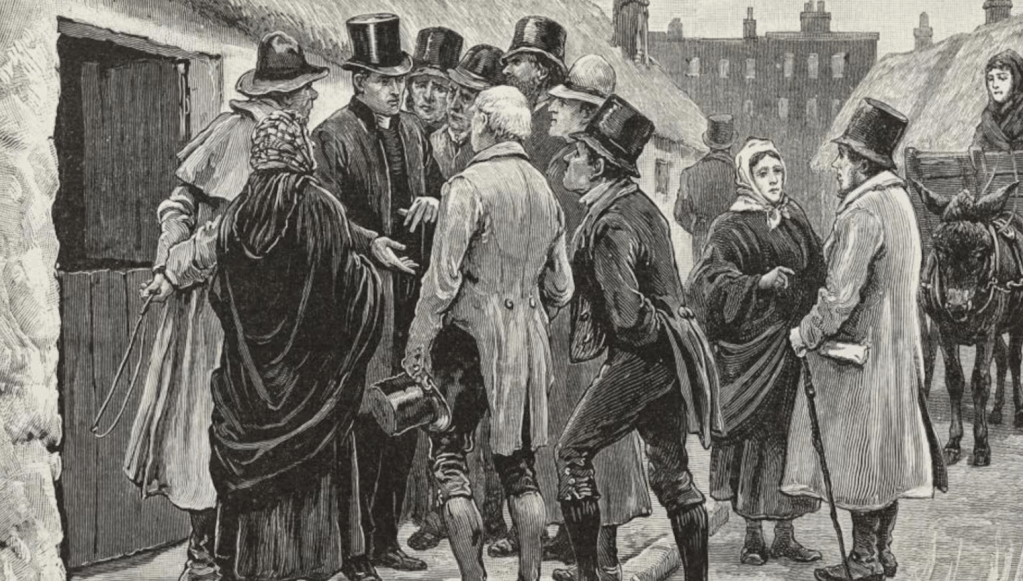

This and the following are selections from Thomas Chalmers on his attitude and outlook on reaching the poor Irish “papists” of his day, both domestically through aggressive, Protestant territorial missions, as well as on the Emerald Isle itself. Much here that is relevant, especially when so many Western nations have swarms of un-Christianized immigrants on our very doorstep.

* * * * *

Chalmers here refutes the notion that the Protestant establishment in Ireland ought to respect parochial bounds of Romanists. No! Parish lines are only relevant for the sake of the Gospel, and ought valiantly to be transgressed when the strong man’s house must be plundered: “We do not say that the maxim has been universally acted on, but it has been greatly too general, that to attempt the conversion of a Papist was to enter another man’s field; and that, in kind at least, if not in degree, there was somewhat of the same sort of irregularity or even of delinquency in this, as in making invasion on another man’s property. In virtue of this false principle, or false delicacy, the cause of truth suffered, even in the hands of conscientious ministers; and when to this we add the number of ministers corrupt, or incompetent, or utterly negligent of their charges, we need not wonder at the stationary Protestantism, or the yet almost entire and unbroken Popery of Ireland. We now inherit the consequences of the misgovernment and the profligacy of former generations. They may be traced to the want of principle and public virtue in the men of a bygone age. Those reckless statesmen who made the patronage of the Irish Church a mere instrument of subservience to the low game of politics—those regardless clergymen who held the parishes as sinecures, and lived in lordly indifference to the state and interests of the people—these are the parties who, even after making full allowance for the share which belongs to the demagogues and agitators of the day, are still the most deeply responsible for the miseries and the crimes of that unhappy land (Chalmers T 1838m; Works 17:304).

* * * * *

“Have we not at this moment an insidious and advancing Popery to fight against, and this in various ways and on various walks of exertion? through the medium of the press; through the medium of our pulpits; through the medium of Parliament; through the medium of those constituencies by which either the present Parliament might be controlled, or future and more christian Parliaments might be formed. Is there no probability of introducing there a thoroughly devoted, even though it should be a very small body of patriots in the highest sense of the term, and fixed upon, not on any principle of secular politics, but because prepared on every fitting occasion to lift their christian testimony, and to take the christian side on every question which involved in it a christian principle” (Chalmers, On the Evangelical Alliance, 1846).

* * * * *

This last selection is taken from Chalmers’ “Evidence before the Committee of the House of Commons on the subject of a Poor Law for Ireland” in 1831. He relates from his experience how the poor were handled in his St. John’s parish mission in Glasgow, from 1819-1823:

“Had you at Glasgow any portion of your parishioners in St. John’s, of a religion differing from the established church of Scotland? A good many; it was one of those parishes in which, from the population having outstripped the established means for their instruction, there were very few indeed who belonged to the established church of Scotland.

“Were there any Roman Catholics? A good many Roman Catholics.

“Were there any of those Roman Catholics in the progress of education within your view? There happened to be one school very numerously attended, to the extent of 300 scholars, within the limits of the parish of St. John; it was a school which, along with two others, was supported by the Catholic School Association that was formed in Glasgow, and we made what we considered a very good compromise with the Catholic clergyman: he consented to the use of the bible, according to the authorised version, as a school book, we consenting to have Catholic teachers; and upon that footing the education went on, and went on, I believe, most prosperously, and with very good effect. From the mere delight I had in witnessing the display and the exercise of native talent among the young Irish, I frequently visited that school, and I was uniformly received with the utmost welcome and respect by the schoolmaster. I remember, upon one occasion, when I took some ladies with me, and we were present at the examination of the school for about two hours, he requested, at the end of the examination, that I would address the children, and accordingly I did address them for a quarter or nearly half-an-hour, urging upon them that scripture was the alone rule of faith and manners, and other wholesome Protestant principles. The schoolmaster, so far from taking the slightest offence, turned round and thanked me most cordially for the address I had given.

“That schoolmaster being a Roman Catholic? That schoolmaster being a Roman Catholic; it really convinced me that a vast deal might be done by kindness, and by discreet and friendly personal intercourse with the Roman Catholics. I may also observe, that whereas it has been alleged that, under the superintendence of a Catholic teacher, there might be a danger of only certain passages of scripture being read, to the exclusion of others; as far as my observations extended, he read quite indiscriminately and impartially over scripture; I recollect, that day in particular, I found him engaged with the first chapter of John.

“Did you meet with any contradiction on the part of the Roman Catholic clergy of Glasgow? Not in the least, for the clergyman was a party in the negotiation; he attended our meetings, and there was a mutual understanding between the clergyman and the members of the committee; nay, a good many members of the committee were themselves Roman Catholics, and I remember, when I was asked to preach for the Roman Catholic School Society, the committee came and thanked me for my exertions, and more particularly the Roman Catholic members of that committee, who were present at the sermon.

“Do you consider that the success of that experiment was owing wholly or in any degree to their reliance upon the absence of any indirect object on your part, or any attempt to interfere with the religious faith of the Roman Catholic children in the way of proselytism? Had they suspected any sort of attempt that was obnoxious to their feelings, they of course would not have sent their children to the school” (Chalmers, Works 16:411-13).

This is wonderful.